30 years of A Hundred Monkeys in 30 minutes

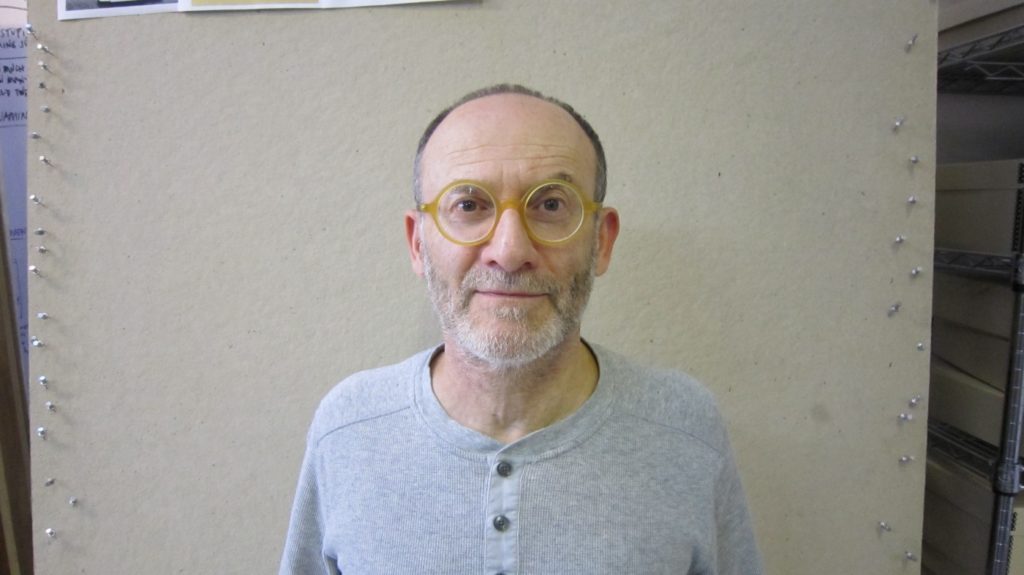

I interview my dad, A Hundred Monkeys founder Danny Altman, on the early days of the company and the evolution of naming.

We try not to dwell on the the past too much around here but every once in a while it’s nice to take a look around and ask, “how did we get here?” 2020 marks 30 years of naming for A Hundred Monkeys. While many creative endeavors are short-lived, this one somehow found the staying power to outlast two tech bubbles, a financial collapse, and, unless we take a serious turn for the worse, a pandemic.

This company is more a part of me than I’m willing to admit. In 1990 I turned six. My dad left his ad agency Altman & Manley to start A Hundred Monkeys. My earliest memory is laying out long rolls of faxes in the hall outside my dad’s office and cutting along the dotted lines. I started naming with LePens on canary legal pads soon after that. Technology has come a long way since 1990, and so has the company.

Eventually, if/when things get to back to normal we’ll throw a party and celebrate the old fashioned way. Until then, here’s a conversation my dad and I had this week talking about the company and how it’s changed over the years.

A note on the format: I’ve been on some podcasts but have never created anything like this on my own. Let me know if you have any production pointers or if this is something you’d like to hear more of. I took the opportunity to do some Marc Maron-style guitar noodling intros/outros.

Links: airlift.fund, don’t call it that

Transcript:

Eli:

Hey, this is Eli Altman, creative director at A Hundred Monkeys, author of Don’t Call It That and Run Studio Run, coming to you today from the guest bedroom in my house, which i imagine is a fairly familiar situation for some of you. I wanted to share something cool with everyone today, something I’ve been wanting to do for a while, which is an interview with my dad, Danny Altman, who founded A Hundred Monkeys and this year, 2020, marks 30 years of A Hundred Monkeys being in business.

Eli:

Definitely the type of thing we want to have a party for and celebrate with everybody, which we will do, not sure when. In the interim, I just wanted to sit down and talk with him about what it was like in the beginning, how the company got started, how he got into naming, and thought that would be interesting and something I also just kind of wanted to have on the record for myself.

Yeah, let’s get into it. Here’s 30 minutes on 30 years of A Hundred Monkeys.

Eli:

Hey.

Danny:

Hi.

Eli:

Cool. I think the main idea we wanted to talk about is just having A Hundred Monkeys for 30 years, which seems like a long time.

Danny:

Yes. That’s about the time it takes to produce a fully formed adult.

Eli:

Are you saying that I’ve just been there for five years now?

Danny:

We’ll just let that one go.

Eli:

Yeah. Take me back to the beginning. As I remember it, you told me that the idea for A Hundred Monkeys was formed at Langer’s Delicatessen in LA.

Danny:

Yeah. I was with my partner at the time, Bob Manley. We had a hybrid advertising design company that we were running out of a studio in Boston. We had a couple of hours to kill before he caught a flight back to Boston, and so we were hanging out at Langer’s Deli and we decided to make a list of all of the naming projects that we had done for our clients. By the time we were finished, there were 40 names on the list, and out of that discussion came the idea to spin that out as a separate business.

Eli:

Where were you living at the time? Were you still in Boston or where you up here?

Danny:

No. I was living in Mill Valley, and we were in LA because a client of ours was doing software for NCR point of sale machines and his test client was the Los Angeles Zoo. Bob and I went to the zoo and then to a delicatessen. That seems like the right order.

Eli:

I was going to say, so you started testing on animals before you switched to humans, but okay. I mean, that’s a lot of naming to be doing at an ad agency, but that also just gives me the sense that ad agencies likely do a lot of naming.

Danny:

Yeah. And to be sure it wasn’t just an ad agency. It was more of a design company than an ad agency, and Bob’s background was in fine arts, and so we were definitely tilted towards the design side. I had always hated advertising, and so I found it very refreshing to be working with designers. If you were to look at a list of the projects that we were doing at that time, it was really all over the map, from corporate identity and brochures, ad campaigns, point of sale stuff.

Danny:

I mean, we basically tried to understand the client and what their needs were and to propose whatever made sense to help them out. In the course of doing that, a lot of things needed to get named, and I guess we looked at it very naturally and without thinking of, well, how do we make money on it or what’s a good name. We just, I guess, looked at it as we did any other design project.

Eli:

How long after that did you start A Hundred Monkeys? Because I imagine there’s still a pretty big chunk of time in there.

Danny:

Yeah. Well, it started out that the name that Bob and I chose for the naming portion of the business was Whatchamacallit. That happened in the late ’80s and we spun that out as a separate business and started marketing it separately. Bob didn’t last that long after that. He had cancer and checked out, so it sort of became my project at that point.

Eli:

Was Altman & Manley still going on at that point or no?

Danny:

No, not at the point where … It, I think, was going on until he died. I don’t even remember what year that was.

Eli:

When it comes to sort of switching from doing naming when it comes up to running a naming company, did those projects feel different? What was new about running a naming company as opposed to doing naming projects at a design firm or ad agency?

Danny:

Well, at the design company, we already had the clients, so it wasn’t a question of setting it up as a separate line of business. If you’re going after naming clients, you need to establish your legitimacy as a naming company. At the time that we were doing that, naming was very new as a line of business and there were very few people who were specializing in that.

Eli:

But I mean, all of the portfolio, the experience, came from projects that you did as part of a much bigger operation.

Danny:

Yes, that’s correct.

Eli:

When you really focused on naming, what were some of the first things that came up for you, or what did you learn? What was different about having that as your focus?

Danny:

You mean after … Yeah, I don’t have a clue. I mean I don’t …

Eli:

How did we get here?

Danny:

I mean, but it was interesting because … Exactly. No, but I mean that’s an interesting question, because when we were doing naming originally it was for clients that we knew really well, for businesses that we understood. The first job became, when we had spun this thing out, was to create a process for quickly understanding who these people were, how they thought about their business, what was important to them, what they were trying to name, what their risk tolerance was. I mean, we had all of those kinds of issues that we needed to build into a standalone business. We weren’t using it as a other business.

Eli:

Right, but I think that’s really interesting to me because, one, it ties into something that you’re excellent at, which is just getting to understand people, getting them to open up, being genuinely curious about what people are doing and why they’re doing it, so I think that played into your hands really nicely, I imagine.

Eli:

But then the other piece of it, to me, is that looking at the business now, our focus seems to be going way more towards that and towards sort of deeper relationships where we know people really well, where we understand what they’re trying to do as opposed to the sort of marketing, get your name out there, work with as many people as you can type of model.

Danny:

Yeah. I mean, the disappointing part was a lot of these people really didn’t give a shit. I mean, they just had a deadline and they needed a name and they found somebody who specialized in it and apparently could deliver names that were creative, trademarkable, et cetera. But they weren’t thinking too hard about it, so at that … Some of those projects were not very exciting from an intellectual standpoint.

Eli:

Did you exceed those expectations and get them to a place where they could really see the value, or was it more just transactional, on to the next one?

Danny:

I think it was more transactional.

Eli:

Then at what point … Because I know, thinking back to what I remember to be the earlier days of the business, it sort of didn’t feel like that was the model. How did you go from that to something that sort of was a little more relationship driven?

Danny:

Thinking more about the process and how to make it more interesting for clients, how to get across the idea that there was a whole world in that oyster.

Eli:

Yeah. Thinking back just to the early days, what were some of your favorite projects or favorite relationships? Where did you really feel like you made a difference for people?

Danny:

I mean, it’s all kind of a blur. I mean, a lot of this kind of overlapped with doing projects and other work at the same time. There were times when it sort of went in and out of being a strictly naming business relative to who my partners happened to be at the time.

Eli:

Yeah. I mean, you’ve had a couple of business partners over the years. I’m curious what you take out of those situations because it doesn’t … There were sort of a few iterations, and I guess my recollection is they didn’t really seem to work out for the most part since Bob.

Danny:

Yeah. I mean, because they were more like business relationships than creative partnerships, and I was always looking for the former, so it was … Yeah, there was some sort of perpetual disappointment built into those relationships. I mean, there were people who came along and thought, wow, this is a cool way to … You can actually make a living doing this. From my standpoint, you can make a living doing anything creative if you have a knack for it and a track record and some talent or whatever.

I never looked at it that way. For me, it was always an excuse to kind of go on the creative hunt and to perform psychological experiments on clients, trying to understand what made them tick, what their tolerance for risk was, what they were really trying to do as opposed to what they said they were trying to, that kind of stuff.

Eli:

If part of the success seemingly of working with Bob was that you both were creatives but operating in different capacities, why did you not want to go back to that well and sort of find another creative partner?

Danny:

Oh, it’s probably the same thing that you hear sometimes from people who’ve been married for a long time to the ideal mate, that there’s a certain feeling that it’s impossible to find somebody that works that well.

Eli:

Okay. And …

Danny:

And the other part of it would be because I have worked with other creative partners since then, but then in that case, the naming seemed like it wasn’t really relevant to the relationship. It’s maybe this whole thing was a function of the relationship that Bob and I had that we could, the way that this came about, because I mean, if we had set out to do this deliberately or two smart creative people got together and decided, oh, let’s have a naming company, I don’t think it would work.

Eli:

But you still kind of kept wanting to give it a shot, I guess, to a point, right? At some point did I become the creative partner? How did that work?

Danny:

Well, yeah. I mean, you kind of showed up and were an astute observer and had your own sort of take on how things should be done, and you started to, I think, deconstruct the process and think about, well, what’s really the smartest way to put this whole thing together.

Eli:

There’s a couple of things in there I think are interesting and sort of worth unpacking. One is about working by yourself versus working on a team and particularly with regard to naming and writing. What are the aspects of that process that are well suited to teamwork and what are the aspects that are well suited to being on your own? Which I think is still an active discussion that we have at the company all the time.

What do you think about that? Do you feel like there’s certain aspects of the work where you really do want to be on your own? And are there parts of the process where sort of having people around to bounce ideas off of, to work on different projects, really ends up being a benefit?

Danny:

I think the figuring out what it is, what’s the real problem, what’s the angle of attack, what’s interesting about it as a creative problem, where do you go to look for answers, strategizing about how do you work most effectively with a particular client. I mean, I think those are really good group activities, and I guess the writing part has always been a solitary exercise for me, with the exception that I always found that art directors and designers had a really great take on writing because it wasn’t their responsibility so they could just muse without penalties.

Eli:

Huh. Well, do you feel like that goes the other way? Because I imagine they wouldn’t feel the same way about you having thoughts on design.

Danny:

Well, yeah. I would just say that working with designers for many years, that was a skill that I gradually acquired.

Eli:

Yeah. That’s interesting that we both kind of have that. We picked that up in different ways, you through exposure in collaborating with a lot of designers at agencies and me through thinking I wanted to be a designer and being one for a little bit and having that same type of exposure. But they’re still sort of essential partners for us because we don’t touch design. Part of that’s about understanding how they work and what they like and how to set them up for success.

Danny:

I think what we share is a deep respect for designers. For me, I came to that because I started working in the world of advertising as a copywriter and turned out to be a business I hated and sought immediate refuge from. The people that I wound up having an affinity for were designers because they were human beings first and maybe problem-solvers in the aesthetic realm second.

I don’t know, I just felt like the question of having a point of view as an individual and also being able to develop a point of view about a problem seemed like a very natural one, so that’s why … I mean, when we’re working on naming problems, it’s a little bit like you’re working on an assembly line, and we’re pretty close to the front end of the assembly line, so that’s a nice place to be. But then you help a client select a name and then somebody’s got to design that whole identity and look and feel and so forth, and you don’t want to have a cool name turn to shit because it falls into the wrong hands.

Eli:

Yeah. We’ve never seen that happen?

Danny:

No.

Eli:

I’m curious what-

Danny:

I mean it has to do with feeling for the craft and it’s like a lot of the way we look at names is to think about the potential and where a name can go and what it can be. And we know that can just as easily become a dud, depending on who gets to perform the operation, so it becomes a really important decision.

Eli:

Well, yeah, and another place where you can start to build strong relationships.

Danny:

Yes.

Eli:

And those strong relationships can bring in work for you. You can bring work to them, but more than that, you can sort of ensure that your work meets a really nice visual system so that it’s not just a cool word devoid of context or aesthetics.

Danny:

Right. Yeah. And also, I mean, you’re starting with the point that a name is a visual too, so-

Eli:

Yeah, that’s a good point.

Danny:

Just how the, how the letters sit there next to each other is the beginning of, or at least one beginning of that process.

Eli:

I’m curious about the relationship between naming and writing because it’s something that is still coming up for us a lot as we take on more writing work and it’s clear that there is a relationship. I mean, it’s both words, just some have higher impact or can go in more places because they’re tiny. It’s also something that we’ve sort of found out that we end up wanting to hire for writing ability. And maybe it has to do with what that says about people’s ability to think through problems or critical reasoning or something like that. But what do you think the relationship is between naming and writing?

Danny:

Well, I think it’s about crystallizing something important about the problem, the proposition, the company, whatever it is that we’re working on. In the old days, when I was an advertising copywriter, I had the reputation of writing extremely short copy. I thought that there was a kind of a natural path from writing extremely short copy and looking at a name as a piece of copy that contains one word. You’re always trying to pack as much as you can into a limited amount of space, and so a name becomes the ultimate writing problem.

Eli:

I think it’s interesting to think about packing a lot into a name because I think sometimes I agree with you that it’s sort of about fitting as much as you can into this small package, but other times I think it’s about being almost protective of what can fit in that space, because if left to their own devices, I think most clients would prefer that a name do five or six things at the same time, even though we all intuitively know that a word or a short phrase can’t be pulled in that many directions at once.

Danny:

Yeah. I mean, I think we’re talking about the same thing. In the case that you’re describing, you’re trying to compact it to the point where you’re using one focal point to convey the message.

Eli:

Mm-hmm.

Danny:

But then after that, I think it opens up. I don’t think we’re looking for robotic or overly simplistic clarity. I mean, there’s always a sense of texture and personality that we’re looking for that comes out the other end. It’s just kind of like how hard can you squeeze the coal to get the diamond.

Eli:

Yeah. And then also talking about the sort of other components of the brand, be it writing or design, that you have lots of opportunities to convey some of these things. Names are better at communicating some things than others. It’s like you’re really, you’re looking for that impact and that emotional reaction and that sort of memorability and at a certain point … And every name just has its own personality, its own sort of sense, given the context. I don’t know, maybe it’s like sometimes you feel what you’re trying to fit into it fights against where you’re trying to get or maybe because, I guess, it sort of takes working on something or naming on something to pull some of this out.

Danny:

I think it’s interesting, too, that we’ve, looking back to the origins of the business, that we went from very broad to squeezing it down to something extremely narrow and now the business has kind of opened up again where we’re starting with the name and then sort of developing, positioning, and messaging and having other things come out of that. There’s a kind of nice symmetry there.

Eli:

Right. Because, I mean, I remember for a while, or at least around the time where I joined, a lot of it was around slimming down the offering, that we did too many things, and because of that, it was really hard to nail down process.

Danny:

Yes.

Eli:

We really just wanted to focus on naming and wanting to make sure we really nailed that and our process really worked, in that everybody at the studio could participate and run projects. Then, I think once you get that ground underneath you and that feels natural and projects are sort of happening the way you want to, then it’s kind of natural to look for something else that’s exciting or something else to figure out.

Eli:

I think one of the things I really enjoy about writing projects is that the writing piece comes naturally, but the explaining writing to people, helping them see the value of it, the process of managing a writing project, the fact that it is more sort of personal and individual relative to a naming project. All these are sort of things that I feel like we’re figuring out in the way that we were figuring out naming process a decade ago.

Danny:

I remember those charts we made, menus of services, and trying to figure that out. It was very complex and I didn’t … I mean, I kind of came at this from, as a therapist once told me, that I had an oceanic personality, so-

Eli:

What does that mean?

Danny:

There was some kind of structure there, but it wasn’t necessarily apparent and it wasn’t necessarily easy to transmit it because it wasn’t written down and hadn’t been through kind of an analytical process to look at it from a number of different sides and so on. I think that sort of represents the beginning of trying to rationalize the business, both for people inside the company and as a marketing proposition.

Eli:

Yeah. When you started this, did you ever think it would last 30 years?

Danny:

I never thought it would last 30 minutes. No. I just think creative businesses are very tenuous affairs. That’s why I have a lot of respect for what you’ve added to the business, because you built things kind of on top of each other in the right order, and so there’s something that feels, it feels more longer-lasting than it ever did to me when I was doing it by myself or even in concert with other people because it was always a somewhat chaotic affair.

Eli:

Yeah. I mean, I guess I’m always surprised that we’re in a pandemic, we’ve survived two bubbles bursting, one economic collapse. I mean, naming feels frivolous relative to those things, but I guess it’s sort of been proven out that that’s not really the case, that even when times get tough, somehow it’s something that people still see value in.

Danny:

Well, yeah. I mean, they have the same needs that they always have. I guess the question is, do they have the resources? I guess we’ve been fortunate in working with companies that have the resources and also with people who understand the importance of constructing the front end in a way that is going to make the things that follow it make more sense.

Eli:

Yeah. It sort of reminds me of … I remember one project we did together a while ago where the client was this ex-Israeli Special Forces guy, and the main thing I remember from our conversation was that he said, “Never waste a crisis.”

Danny:

Yeah.

Eli:

To me, it’s just sort of when something like this happens, that you think that, well, a lot of people see opportunity and want to start new things or have their opportunity taken away from them and need to create something new, that every time that the deck gets shuffled, there’s an opportunity to create something new. And we sort of exist at that place where people are creating something new.

Danny:

I think that’s right, because I think a lot of the economy is in a state of paralysis and some of that’s personal and some of that is a lot of businesses are hurting. But somewhere in there, there are a lot of opportunities that are being created, and I think that those are the people that we attract.

Eli:

Yeah. What are you working on now? You want to talk about Airlift a bit?

Danny:

Sure. I was thinking about this never waste a crisis because I’ve been working for the last couple of years on a project called Airlift, and we are a nonprofit that is not inventing any new wheels. What we’re really doing is finding the smartest, most effective nonprofit groups that are indigenous to battleground states and getting them the funding that they need. They’re already good at what they do. The thing that they don’t have are the resources to amplify the exciting things that they’re doing.

Eli:

Yeah. Where can people find out more about Airlift?

Danny:

At our website, which is airlift.fund, F-U-N-D.

Eli:

Great. All right, well, I think that’ll do it for today. You good? Anything else you want to add?

Danny:

Yeah. I just began to read the third edition of Don’t Call It That, and it’s very exciting. There’s a lot of new stuff in there, and I agree with you, it does feel a lot more like a workbook.

Eli:

Nice. I’ll include a link for that one, too. All right.

Danny:

All right.