New word, who dis?

What happens when we see words that are unfamiliar to us — in naming and beyond

Ingredients, technologies, viral strains, street names, animal breeds. We see new words constantly—so much so that we don’t always notice when it’s happening. Our brains become accustomed to new words quickly after a bit of language processing, which of course isn’t required for words we already know.

At A Hundred Monkeys, we like names that get people out of their comfort zone. Sometimes this means that in a naming presentation, a client is seeing a certain word for the very first time. I wanted to take a closer look at what these names require of our brains before they can become part of our vocabulary. Spoiler: it isn’t much.

In our creative studio, we use the term “empty vessel” to refer to names that are a bit more obscure. They’re “empty” because they don’t come pre-loaded with meaning for most people — so with the help of other brand elements (like visual identity, copywriting, etc.), there’s potential to fill them with meaning and build a unique story. Empty vessels might come from the depths of an anatomy textbook, or from typography or a botanical field guide—like Lacuna, Versal, or Avens, respectively. We love empty vessels that have real meaning, as opposed to made-up words, because there’s a more rewarding story for those who look for it.

Of course, these names exist on a spectrum. Some empty vessels are meant to be enigmatic and mysterious, while others offer a clearer landing zone for some meaning. It’s the difference between Eero (a Finnish given name) and Starbucks (a literary reference: Pequod’s first mate in Moby Dick). One is a name that sounds unique to American ears, while the other contains two incredibly common English words.

There are pros and cons to every type of name on this spectrum. Different levels of familiarity will call for different amounts of storytelling, and less familiarity might mean more emphasis on the appearance of a word.

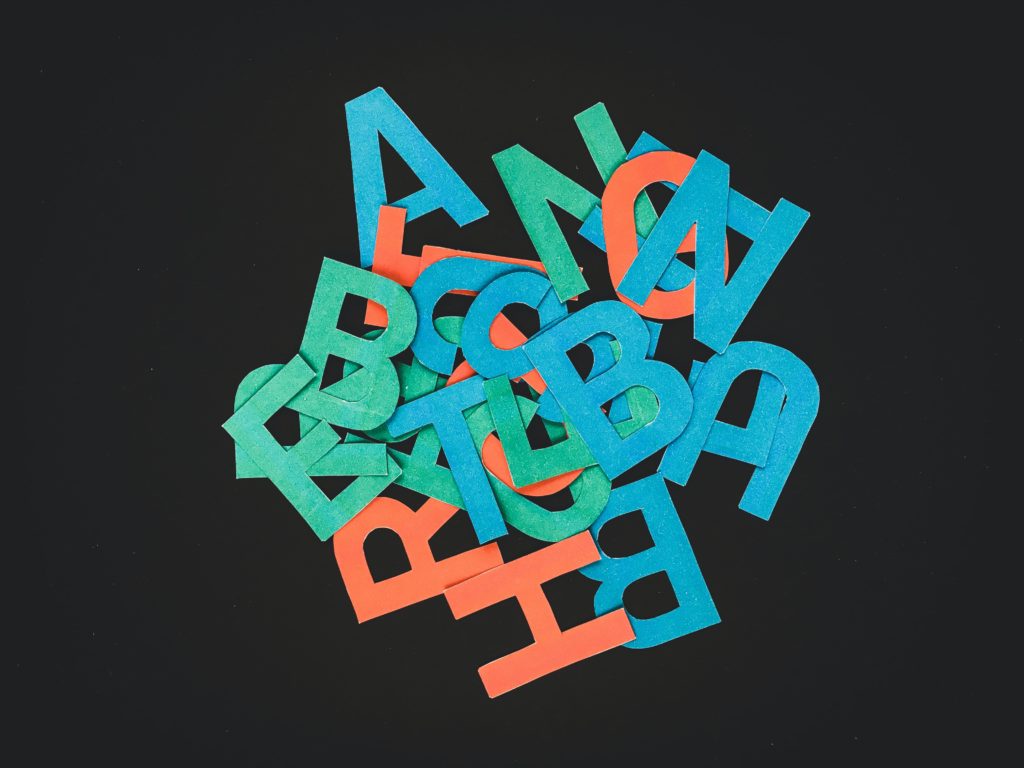

Seeing pictures

A Georgetown University Medical Center study found that our brain is tuned to recognize familiar words as pictures, rather than as collections of letters. So when faced with an unfamiliar word, our brain essentially adds it to a visual dictionary — allowing us to recognize that complete word, or picture, going forward. No surprise, this is what helps us read quickly.

Seeing new words—maybe even more so than hearing new words—is critical to learning them. Since our brain is looking to draw meaning from visual patterns, it makes sense that we’d look for similarities between familiar and unfamiliar words. In naming, we see this whenever we present empty vessels. Without an immediate meaning to grab onto, a client might be reminded of a word with similar spelling or letterform. This can help or hurt a name, and it’s human nature. It turns out, they may just need time.

Time is everything

Another study has shown that our brain officially “records”, or learns, new words within about an hour or two of exposure. This study uses “pseudowords”: made-up words that don’t resemble anything else in sound or meaning. Once a pseudoword is given meaning, participants are able to recognize and remember it more easily.

While we don’t use pseudowords in our naming, it’s logical that an obscure or unfamiliar word might operate similarly.

In a naming presentation, we typically ask for gut-reaction feedback. Gut reactions are valuable because that’s how most people come into contact with brand names in the world. However, gut reactions may not hold the same value for an empty vessel. Based on how our brain operates, we need a bit of time and context in order to store (and then evaluate) a brand new word.

Luckily, when a name is released into the wild, there are plenty of ways to help get the story across quickly—from visual treatment to taglines.

Knowing how the brain reacts to new words helps us approach conversations about these names, but it’s also a reminder of how powerful they can be. We’ve seen that they are just as memorable, if not more so, with the help of a thoughtful and compelling story. They may also face fewer bumps in the trademark road.

They come with some creative risk—freeflying without the parachute of ubiquity—but that risk should be weighed by things like brand positioning and competitive landscape, not by a fear of something different.

Thanks to Ben Weis and Patrick Keenan