The Names They Are a-Changin’

From bridges and post offices to libraries and military bases, from public parks and streets to landmarks and schools there are many names that populate our world and form the nominative fabric of our communities. It is important to employ names that reflect the cultures, values, and positive stories of our communities.

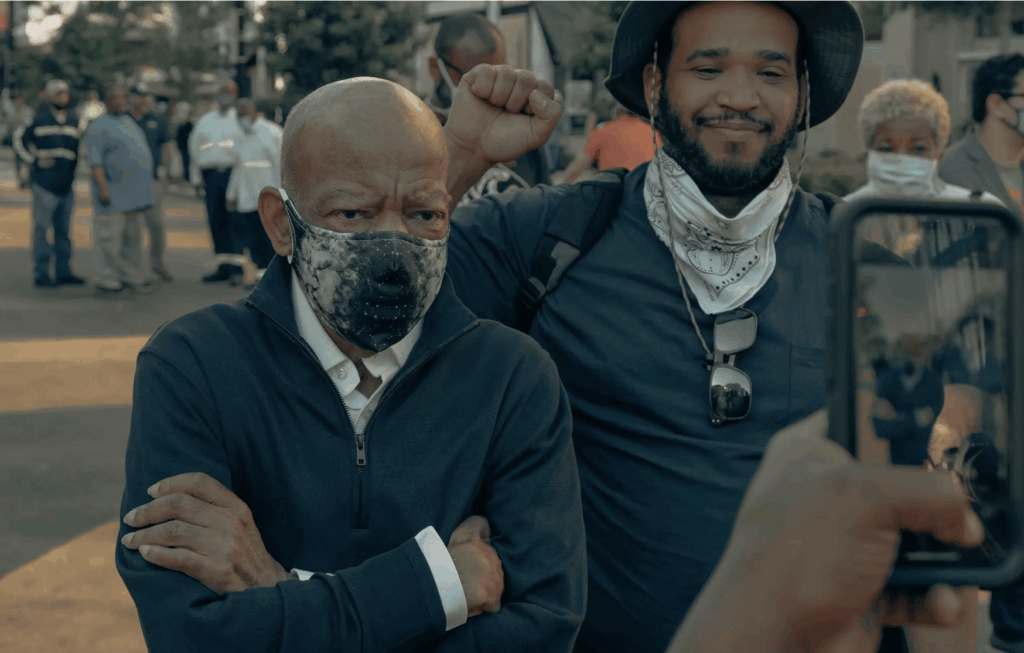

In recent months, we have witnessed major cultural shifts and maybe even participated in remarkable societal change. While citizens throughout the world are making their voices heard, one of the topics that has risen in the collective consciousness is naming. Specifically, the naming (and renaming) of public spaces, public buildings, and publicly funded institutions that have held worrisome or explicitly offensive names for far too long. Let’s take a look at several fixtures of our shared, public spaces that have featured problematic names and see what changes are being made.

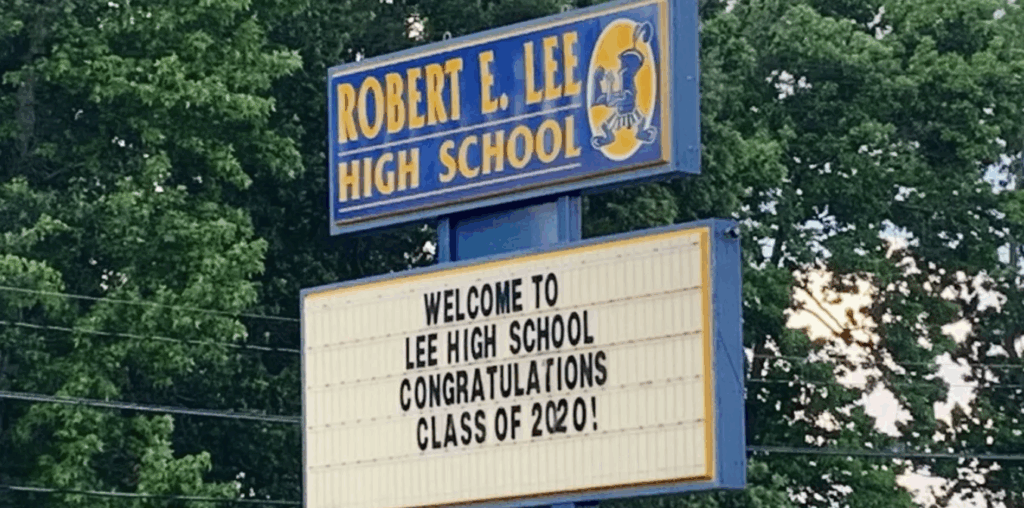

Recently, the United States House of Representatives lost an iconic leader in Rep. John R. Lewis. It was a sad day in the ever-progressing march for Civil Rights, but offered a chance to remember and honor Rep. Lewis’ contributions by memorializing his name. While discussions of multiple bridges being named for Rep. Lewis continue, one high school in Fairfax County, Virginia has already voted to rename itself after him. The high school’s former name? Robert E. Lee High School. By any standard, Lee’s name is symbolic of division, hostility towards the United States, and emphatic support for slavery. Therefore, the high school’s name change is a glowing success for current students and recent graduate Luna Alazar who explained, “we are a tremendously diverse community with strong ambitions and remarkable unity. However, we were named after someone who didn’t represent us at all.”

It is common for United States Post Offices to be designated with names of local or famous people and nearby geographic or man-made features that are intended to match the name of the place or community it would serve. It seems reasonable, then, that a petition was recently started in San Diego, California to change the name of Andrew Jackson Post Office. The name is understandably offensive for Jackson’s clear connections to slavery, the Trail of Tears, and ethnic cleansing. It also raises some questions as to why a post office in Southern California would be named for Jackson. California wasn’t even a state until 13 years after Jackson left office and 5 years after he had passed. It seems the USPS parameters referenced above are a bit askew in this case. While the petition has suggested Harriet Tubman as an option for a new name, this opportunity could also afford San Diego a chance to promote a local civil rights hero or cultural figure.

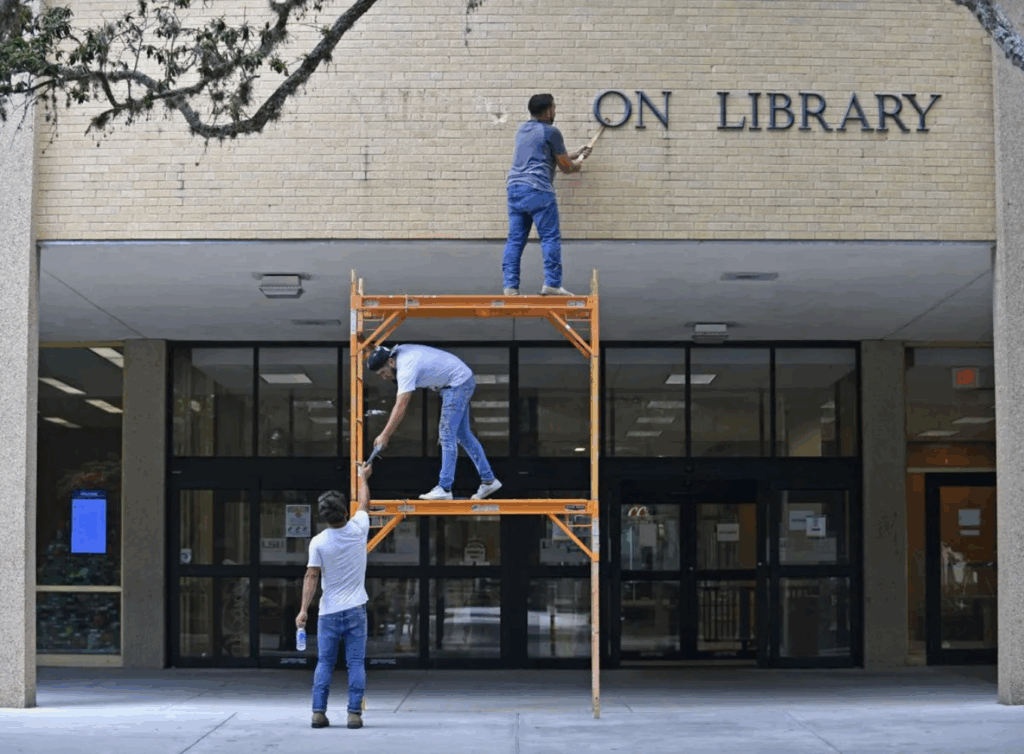

Some places of higher learning are dealing with negative naming legacies that are more recent than the Civil War or Indian Removal Act. Earlier this year Black student leaders at Louisiana State University started a dialogue with the administration to bring more racial justice to their campus. They ultimately met with university officials and asked for the removal of the name Troy H. Middleton from LSU’s main library building. Middleton served as president of LSU from 1951 to 1962 and opposed integration throughout his tenure — even writing a letter on desegregation to the former University of Texas chancellor in 1961 saying, “LSU still kept black students ‘in a given area.’” The LSU Board of Supervisors has voted unanimously to remove his name and a school committee is now in place to evaluate every building’s name at LSU. For the immediate future, the library will be known only as LSU Library while a committee is formed to select a permanent name.

Among the 10 U.S. Army installations named for confederates, three bear special priority for renaming. Fort Bragg (N.C.) is named for Gen. Braxton Bragg who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. By definition, Bragg was treasonous to the Union and should be disqualified from having his name on the single largest United States Army base. Fort Benning (Ga.) was named for Gen. Henry Lewis Benning, a Confederate officer who was “such an enthusiast for slavery that as early as 1849 he argued for the dissolution of the Union and the formation of a Southern slavocracy.” Finally, Fort Hood (Texas) was named for John Bell Hood who resigned his commission in the United States military and became a Confederate captain after the Civil War began — he even led troops on the losing side at the Battle of Gettysburg. Fort Hood has been specifically petitioned to change its name in honor of Roy P. Benavidez, an Army Special Forces master sergeant born in South Texas who received the Medal of Honor for heroism while wounded in the Vietnam War. Despite retired U.S. generals encouraging the removal of confederate names from U.S. bases, and the Defense Secretary and Army Secretary both saying they are “open to a bipartisan discussion on the topic,” the President has completely refused to entertain the idea of “renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations.” Ironic given he’s supposedly a fan of “winners.”

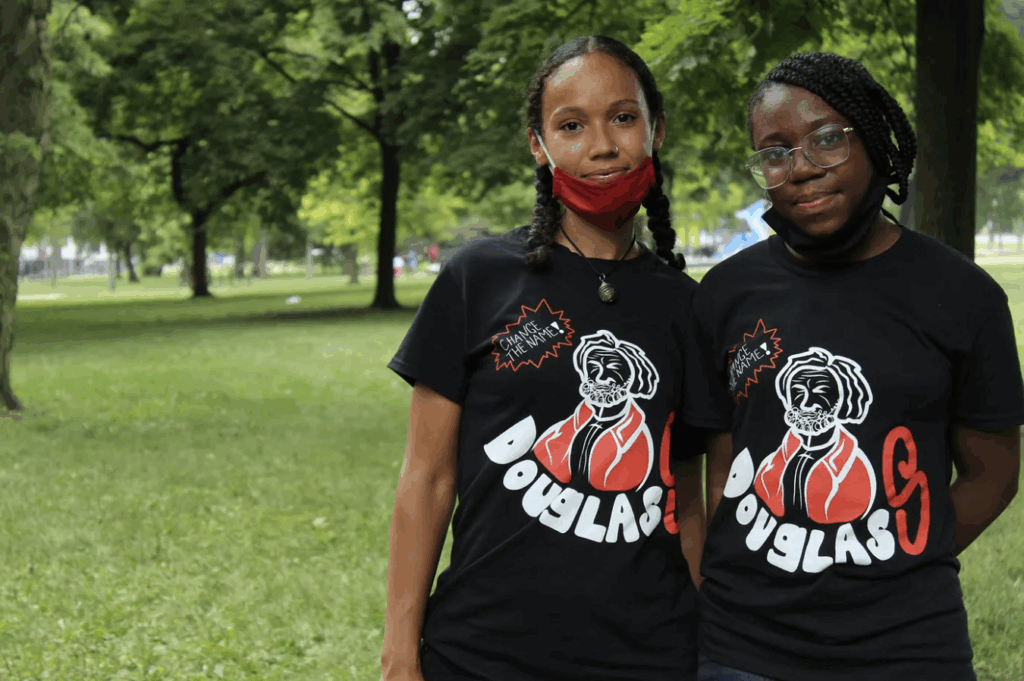

In rare cases renaming can mean merely changing a single letter, but that simple change can make all the difference. On Chicago’s west side, students campaigned for years to change the name of Douglas Park to Douglass Park. The former namesake was Stephen A. Douglas the politician, lawyer, and plantation owner from Illinois who was at best ambivalent about slavery and advocated for “popular sovereignty.” Happily, the park now celebrates the writer, orator, and statesman Frederick Douglass who escaped from slavery and led abolitionist movements in Massachusetts and New York. These reconciliations are a source of inspiration and reminders that we must make demands of our institutions. As Douglass himself said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

As we experience a time of national reckoning over naming of our public spaces, it’s important to remember that names can have a real effect on people — how they feel, how they behave, how they understand and interact with the world around them. It is natural and cathartic, even therapeutic, for communities to remove names from their public experience that represent people who fought to preserve slavery and uphold white supremacy. While the name changes above represent specific transformations from a racist past to an inclusive future, changing names alone does not indicate progress. We need to understand why these changes are necessary and reflect that learning in other parts of our lives.

Find further information about name changes occurring in the wake of the George Floyd protests here.

Thanks to Ben Weis and Patrick Keenan.