The Proof is in the…: Why Feats of Service Make an Impact

A few months back I needed to have the oil changed for my car — a nearby auto shop happened to be the best reviewed so I drove over. The mechanics were polite and gingerly set to work on the request. A few minutes later one of them beckoned me back over to the car. The tech delicately held out the dipstick, showing me that the oil was new and in the proper range, and waited for my approval. “Looks good. Thanks!” I said. He returned the dipstick and closed the hood. Transaction complete.

As I drove off, I recalled the online reviews for this shop were full of references to their helpful employees and several even mentioned that they made a rule of showing patrons the oil level after an oil change. Though I had been prepared with this information, when I experienced it myself I was still struck by it — this feat of service. It felt forthright, considerate, and personal.

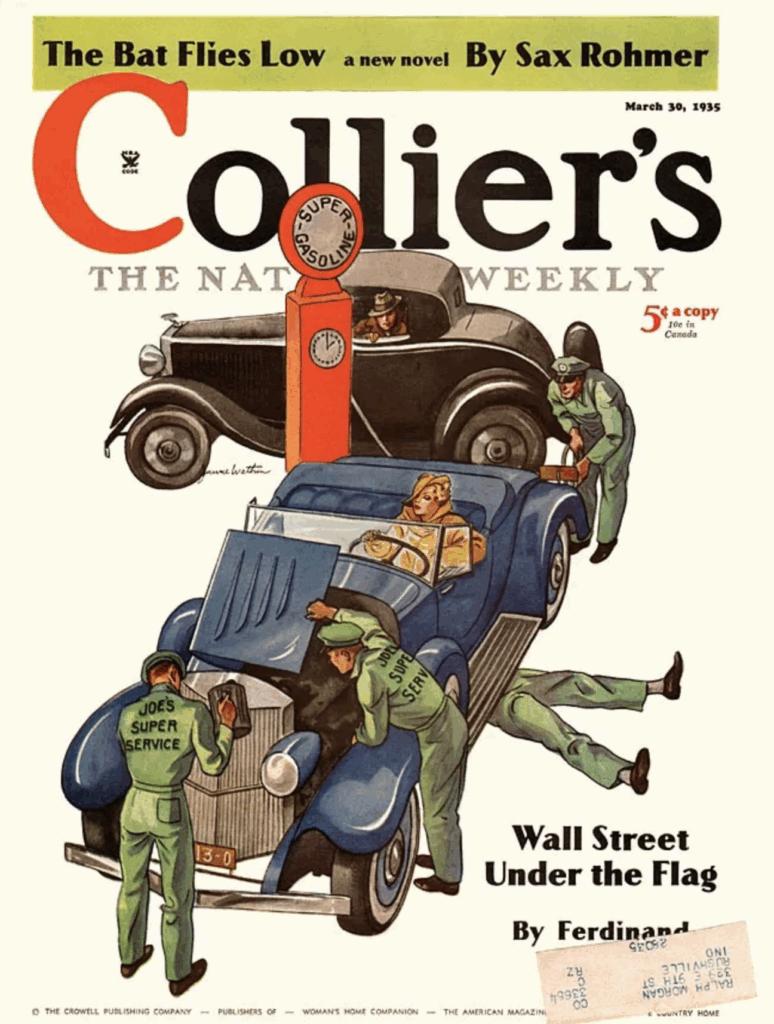

Sometimes these feats of service feel traditional, even quaint — like a service-oriented gesture that one of our parents remembers from the ’50s or ’60s. They conjure a time that has been idealized for us in mass culture and personal anecdote. Such actions can also show commitment to broad reliability based on getting the details right. For instance, if I had been looking forward to the level of care that I had read about in the reviews, but then got a tech who skipped steps or appeared to merely go through the motions, I could reasonably wonder about the more essential details of the work he was doing on my car — or if I was catching him on a bad day.

There is something specific about the power of the visual test in this example and others like it. Think of the deli worker slicing pastrami to a certain thickness and offering a piece to the patron to get their approval. Consider tasting a sample of fresh fruit or vegetables at the farmers market, the farmer themself will likely be concerned with giving you a delicious morsel of what they have to offer. Sommeliers go as far to offer multi-sensory experiences for expensive wines: they provide you with an opportunity to smell, sip, and see the wine, and even inspect the cork for scent and integrity. Whenever you can offer this kind of visual or substantive proof of quality, it has weight. And it can show you care.

All such feats of service or visual tests are indicators of technical proficiency or proof of product. In most cases the performative aspect of such a demonstration indicates the kind of care and attention to detail a business is going to offer its customers.

I don’t know that I have an answer for how brand or creative shops can prove themselves in this manner. In spite of the many “Mad Men”-style jokes about how the marketing and advertising “sausage” is made, I doubt you can get many shops to split open the casing. However, I think at least pondering your work for opportunities to share feats of service would suit many agencies. It could set them up to be more insightful, empathetic partners to their clients.

One could offer explicated examples of past work, unedited testimonials from former clients, or even show how their process has evolved while learning from past mistakes.

I think being fundamentally sensitive, thoughtful, and precise with your language would be a good place to start. There’s power in pursuing the goals of considerate service, and making a promise to yourself and your future clients to refine how you listen, communicate, and adjust for their unique needs.

Thanks to Eli Altman and Patrick Keenan.